The story begins in 1980 with a chance find on John Dixwell in the British Museum, then resumes in New England several decades later with an old key handed over to the author in a plastic bag. Sarah Dixwell Brown had resolved to ask her father about the ancestor whose name always seemed to produce a certain sense of alarm and embarrassement when mentioned in conversation. Now, suddenly, she is presented with the key to Dover Castle the regicide Dixwell took with him as he fled England after the Restoration of the Stuarts to begin life as an exile. Inspired by the heirloom and Ezra Stiles’ History of Three of the Judges of Charles I (1794), Brown, who carries her seven greats grandfather’s name as her own middle name, decides to travel back to England to uncover as much as she can about her ancestor’s history – still torn whether to be embarrassed or proud of his deed.

John Dixwell (c1607-1689) was one of the judges who tried Charles I for treason and sentenced him to death after he had been defeated by the parliamentarians in the Civil Wars. When the Stuarts were restored to the throne in 1660, many regicides fled the country to escape reprisals by the monarchy. Dixwell initially fled to continental Europe and likely stayed in the German town of Hanau, near Frankfurt, for a while before deciding to make his way across the Atlantic to the American colonies. When he left Dover, where he served as governor of the castle, he took the key that would be passed down in his family from generation to generation before landing in the hands of “Dixie” Brown.

An intensely personal book

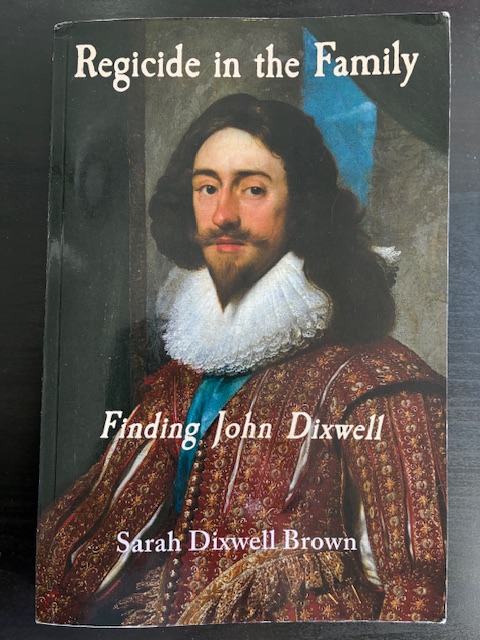

Her Regicide in the Family: Finding John Dixwell (Levellers Press, 2022) is an intensely personal book. It combines family history with the history of the English Civil Wars and the fate of the regicides who had to leave their lives in England behind to start anew in a foreign country. As she crosses the Atlantic in the opposite direction and dives into her ancestor’s past Brown also gets to know England from the perspective of an American. We follow her through London and by train across the country as she encounters England’s magnificent libraries and eccentric archivists and many other friendly people ready to help with her quest. Brown’s story is engaging as she reports on the excitement felt by the researcher who just made a new discovery and on the frustration when the research stalls or the library closes.

Brown’s book is as much about the research process as it is about the content. At times I was getting impatient with her narrative and wanted her to cut to the chase to see if she might have discovered something that might help me move forward with my own research. I was not sure I wanted to know quite as much about improvised meals eaten at the Penn Club, where I stayed many years ago myself when doing research for my PhD. And yet, all these little details made her story all the more relatable. The fact that Dixwell was her ancestor also meant she cared rather more about the circumstances of his life and his relationships with his extended family than an unrelated academic researcher might have done. She shows the regicides not as political figures, but primarily as people – with parents and siblings, wives and children, and daily lives to manage.

Life in exile

Some of these regicides went to continental Europe, others to the American colonies. Most of them would never see England again. Others, like John Barkstead, Miles Corbet and John Okey, were captured by agents of Charles II’s government and returned to England only to be tried and executed as traitors.

Dixwell was lucky. He made it safely to New England, assumed a new identity and lived for several more decades, hidden from Charles II’s agents, as James Davids in New Haven, Connecticut. He was taken in by Benjamin Ling and his wife Joanna, and after Benjamin’s death married his widow. Three years after her death, Dixwell, alias Davids, married Bathsheba Howe with whom he had three children, only two of which lived into adulthood.

Dixwell’s descendants became silversmiths and ironmongers, and, in a later generation, merchants and schoolteachers. One, Epes Sargent Dixwell, in the nineteenth century passed on some of John Dixwell’s papers to the New Haven Museum for safekeeping. But there are many other traces still of Dixwell in New England, from monuments to street names – and of course his descendants, some of whom still live close to where he first arrived on American shores.

The extraordinary story of an ordinary man

In the end, the story of John Dixwell turns out to be the extraordinary story of an ordinary man, who happened to be one of King Charles I’s judges, a regicide, in his younger years. The rest of his life would be determined by the consequences of this one act.

But Brown’s story also connects the past and the present, as it reminds its readers of the complex historical links between England and its former colonies. Furthermore, the author is always conscious of the fact that the ideas of liberty, the rule of law and religious freedom English republicans had fought for in the seventeenth century found their way into the American Constitution – a constitution which was under threat at the time of her writing of the book, and which is under threat again now.

Sarah Dixwell Brown, Regicide in the Family: Finding John Dixwell (Levellers Press, 2022).

gma